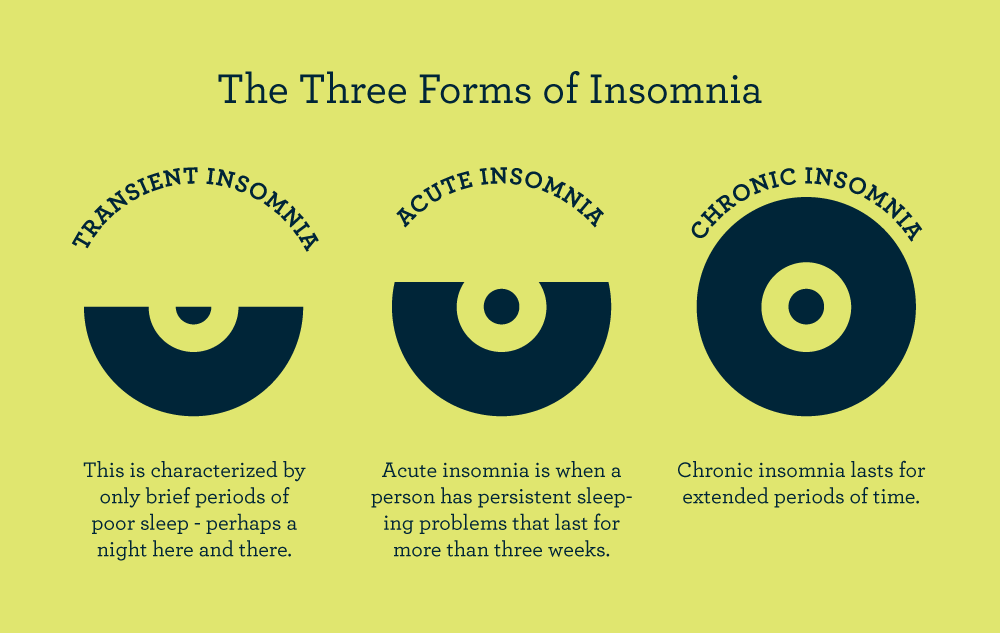

Model 2: The Three Factor Model (1987)

This model is also known as the ‘Spielman model’, ‘Behavioural model’ or the ‘Three P model’. The three P’s stand for:

- Predisposing factors: genetic and physiological

- Precipitating factors: environmental or psychological stressors

- Perpetuating factors: behavioural, psychological, environmental factors that inhibit someone from getting back into normal sleep patterns.

Essentially, this model described how acute insomnia can become chronic.

More specifically, the three P model suggests that insomnia occurs in relation to pre-existing (trait) factors, and life stress (also called perpetuating factors) we may be encountering.

Moreover, chronic insomnia, based on this model, happens as a consequence of inadequate coping behaviours (perpetuating factors).

We all have our own ways of coping with certain problems in life, however when it comes to insomnia much of our predisposing factors have a great role to play.

For example, these traits can include overthinking or over-worrying, along with social pressures that force us to sleep at certain sleep schedules.

When we say ‘perpetuating factors’ what this really means is the various behaviours adopted by an individual which are put in place to compensate for loss, or lack of sleep.

One method of this ‘sleep compensation’ is the idea of “sleep extension“.

In this scenario, those suffering from insomnia will ‘make up sleep” by napping and/or heading to bed early, and/or getting out of bed later.

These aspects of an insomniac are carried out to essentially ‘recover lost time sleeping’.

But there’s a catch to these varying approaches to ‘sleep extension’.

They can fool the insomniac by making them think that extending sleep is a good, and acceptable strategy to eliminate insomnia.

Secondly, it places some emphasis on the idea that having this additional sleep will diminish the symptoms associated with insomnia.

Once again these symptoms can be anything from focusing and concentration difficulties to memory problems.

The true result of this “sleep extension” is far more damaging.

It leads to something known as a “dysregulation of sleep homeostasis“.

This homeostasis refers to a kind of “internal clock” or timer that drives a pressure for sleep based on the amount of time that has elapsed since your last sleep episode.

No doubt, sleep extension approaches to ‘recover’ from lost sleep greatly impacts our internal sleep homeostasis self-timer.